Inflation concerns are justifiably widespread. Although supply-chain problems dominate the headlines, what is most unnerving is the seeming indifference of economic policy officials: The prices of everything—from groceries to houses, commodities to wages, and health care to stocks—are surging higher.

Nonetheless, the Federal Reserve is shockingly still debating about tapering quantitative easing and whether the federal funds rate should be raised in 2022, 2023, or perhaps even later. Fiscal authorities appear equally oblivious, focusing solely on passing two more, massive spending packages that total nearly $5 trillion! If our leaders, responsible for ensuring price stability, refuse to help moderate current inflation pressures, won’t this end badly?

Fortunately, as illustrated by the accompanying charts, “private-sector policy officials” are on the job and have been fighting inflation since last spring! While it is impossible to know if these early intervention efforts will be enough to eventually temper the inflation rate, there is some hope for a good outcome despite monetary and fiscal authorities’ AWOL responses.

Private Policy Officials To The Rescue?

The Federal Reserve and Congress are not the only players who implement economic policies. Private economic citizens, making independent self-interested decisions, also impact the degree of restrictiveness or accommodation ultimately provided by monetary and fiscal policies.

The collective liquidity, investment, and debt propensities of companies, consumers, and financial institutions have a substantial bearing on the degree of monetary growth and the level of interest rates. Likewise, because of the nature of automatic stabilizers built into fiscal policies, the pace of economic growth often meaningfully alters the overall size of deficit stimulus.

Faster economic growth improves tax receipts and lowers social welfare expenditures, automatically lessening fiscal stimulus. Conversely, slower economic growth inevitably expands fiscal juice. This year, “private-policy officials” have played a particularly large role in the size and effect of both monetary and fiscal-policy accommodation.

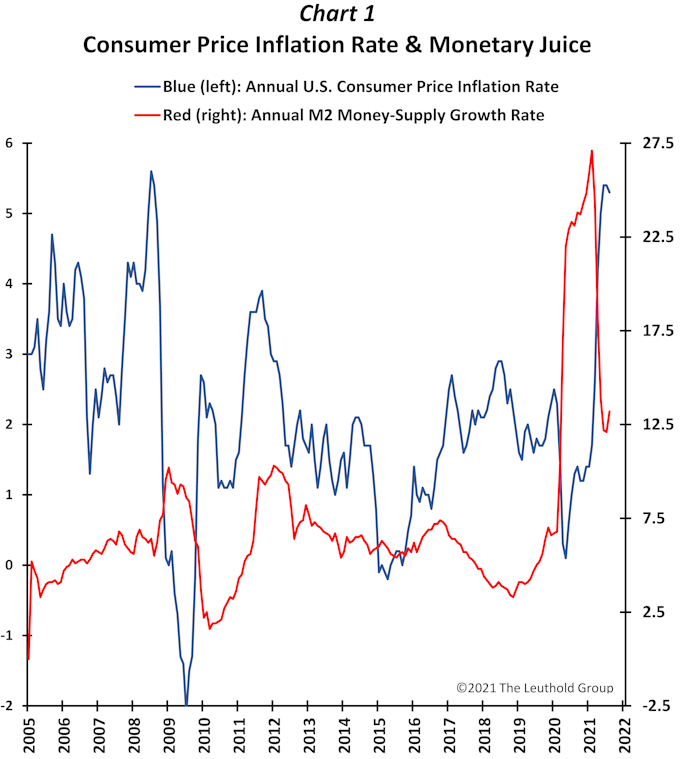

Chart 1 overlays the annual pace of consumer price inflation with the growth in M2 money supply. While not a perfect relationship, money-supply growth has historically guided inflation trends.

For example, the money supply increased in 2006, and inflation followed in 2007. Monetary growth surged again in 2010, and inflation took off in 2011, and, similarly, the money supply accelerated in 2019 before inflation picked up in 2020.

Officially, the Federal Reserve has not yet acted in any capacity to contain monetary growth. Nevertheless, as shown in Chart 1, private-policy officials have slowed money-supply growth significantly since February.

The annual growth in the M2 money supply has dropped from near 27% in March to about 13% today. Likewise, the Federal Reserve’s annual growth rate in the overall balance sheet (i.e., what is utilized to implement quantitative easing, not shown in the chart) has collapsed from about 80% in February to less than 20% at present. That is, monetary policy has moderated considerably during the last six months, and, if history is any guide, this financial restriction should help alleviate inflation pressures in the coming year.

“Officially,” the Federal Reserve is unresponsive and appears significantly “behind the curve” relative to inflation. But “actual” monetary policy has been responsibly leaning against inflationary pressures for months and may arguably be ahead of the curve.

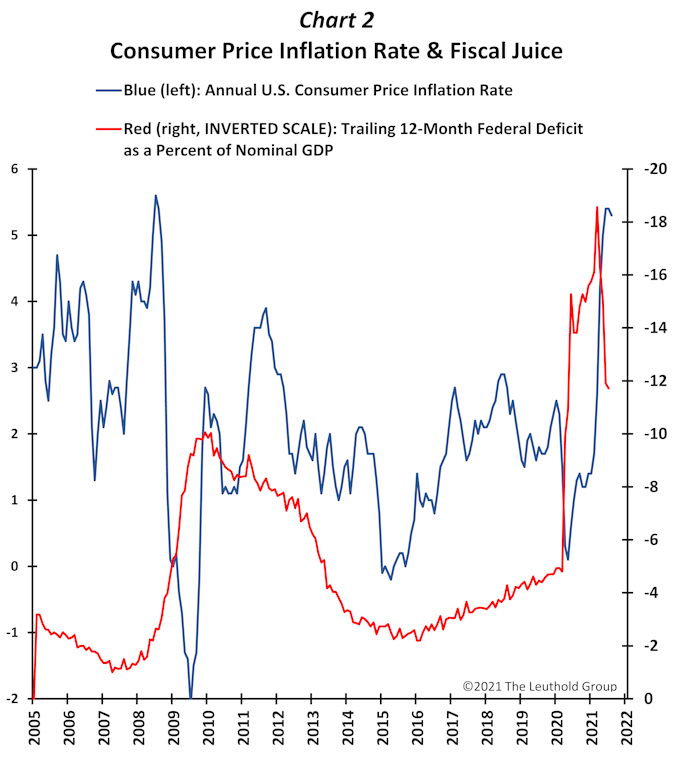

Surprisingly, fiscal policy has also been tightening since March (Chart 2): The deficit-to-GDP ratio fell from about 19% to under 12% in July. Thus, while Congress attempts to reach an agreement about additional stimulus packages, fiscal juice has already contracted by nearly 40%!

As shown, like monetary policy, major expansions in fiscal stimulus have typically led to faster inflation. For example, deficit spending surged in 2008-09, followed by an inflation pick-up during 2009-2011. Similarly, the deficit/GDP ratio spiked in early 2020 before inflation surged later in 2020-21.

While Congress will again soon add to “official” fiscal stimulus, recent months’ sizable reduction in “actual” fiscal accommodation should support monetary tightening and help to calm inflation pressures in the coming year.

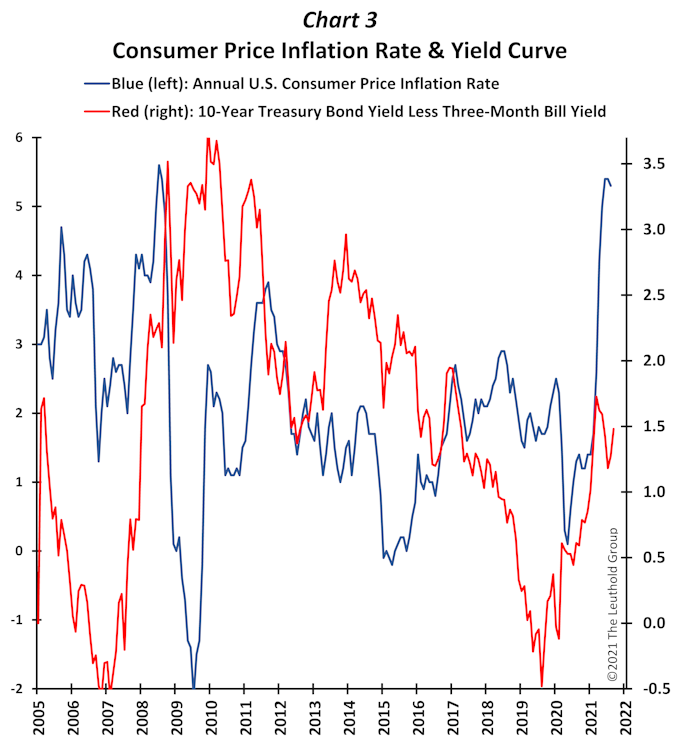

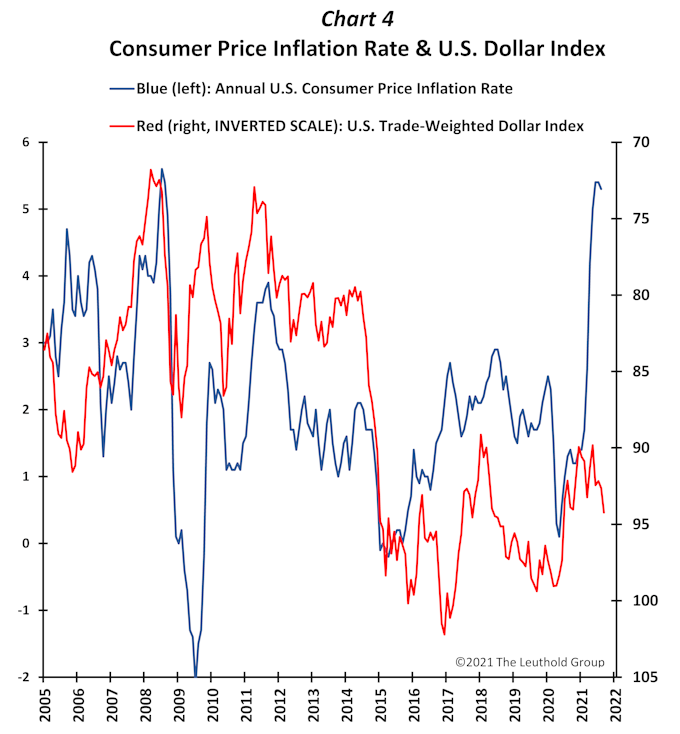

As shown in Charts 3 & 4, the fight against inflation is also getting some assistance from bond yields and the U.S. dollar. So far in this expansion, the degree of yield-curve easing is far less than it was in the last expansion or compared to many previous post-war recoveries (Chart 3).

The yield spread between the 10-year bond and the three-month bill is only about 1.5% compared to peak levels above 3.5% in 2008-11. Indeed, the degree of this expansion’s stimulative curve steeping is only about one-half of its peak level in every recovery since 1970! That is hardly an interest-rate structure that signals a runaway inflation problem.

Moreover, the 10-year yield has nearly tripled from its recessionary low to the current level of 1.5%. Although the yield is very low compared to historical norms, its relative increase since the recession is still jarring.

Finally, as illustrated in Chart 4, the U.S. dollar has strengthened some in recent weeks and has remained fairly robust throughout this expansion. A strong dollar is a significant disinflationary force. Unlike where it traded between 2005 and 2015, if the U.S.-dollar index stays above 90, it should help calm inflation fears next year.

Summary Comments

Supply-chain problems will likely be problematic well into 2022, and inflation jitters seem destined to intensify again. Indeed, in the ensuing months, the long-overdue stock-market correction could finally be initiated by renewed inflation and fear of Fed tightening.

However, even though “official” monetary and fiscal authorities are seemingly blind when it comes to potential inflation risks, “private” economic-policy officials began to ensure months ago that inflationary pressures would not become systemic.

The sizable tapering in monetary growth and significant decline in fiscal stimulus since February—combined with higher bond yields, a relatively modest steepening in the yield curve, and a relatively strong U.S. dollar—are pointing to a more restrained inflation environment in the coming year.

Perhaps bond investors are already reflecting the efforts of private-policy officials and suggesting a favorable outcome for inflation. Despite the breakout by 10-year bond yields, embedded bond-market inflation expectations remain range-bound.

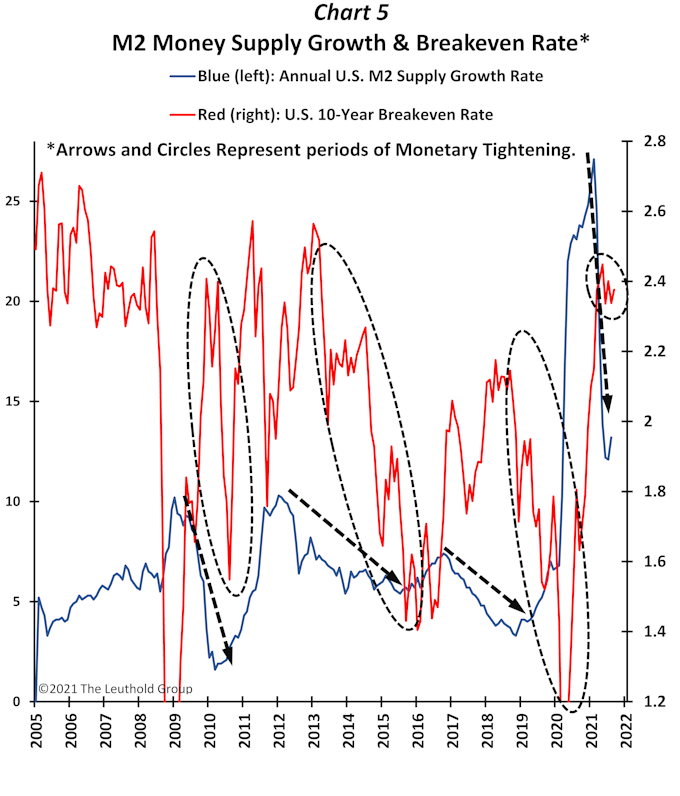

As Chart 5 illustrates, the pace of monetary growth has traditionally guided the 10-year breakeven rate (i.e., a proxy for the bond market’s sustained inflation expectation).

Thus, it is very encouraging that the breakeven rate again seems to be trailing behind economic-policy tightening. The breakeven rate peaked in May (two months after the annual M2 money-supply growth rate) and has been flat since then.

Will inflation expectations fall even further next year, in line with recent monetary and fiscal tightening? That is, could 2022 be the year of “VC&I”: Victory over both Covid and Inflation?