As the Federal Reserve keeps raising interest rates and the 10-year U.S. Treasury yield nears a seven-year high, investors wonder what yield level will bite the stock market? This may be the wrong question. It may not be how much yields rise, nor any specific yield level which ultimately tips the stock market. Rather, the impact of rising yields on the stock market has historically depended on Wall Street’s state of mind.

The correlation between movements in the stock market and yield changes in the bond market describes an investor mindset which provides a good indication of when rising yields become a threat for equity investors. Recently, this correlation and what it implies about Wall Street’s disposition is undergoing change, suggesting the vulnerability of the stock market to rising yields is worsening.

The Stock-Bond Yield Correlation

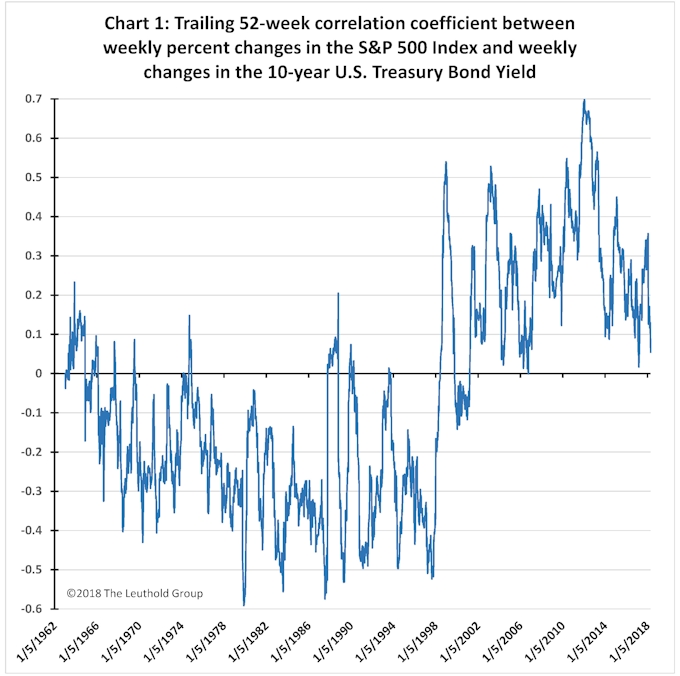

Chart 1 illustrates the trailing 52-week rolling correlation between percent changes in the stock market and yield changes in the bond market since 1962. This correlation has varied over time ranging between -0.60 to +0.70. Between the mid-1960s and the late-1990s, the correlation was mostly negative, but it has been above zero, for the most part, since 1998.

We believe this correlation reflects the prevailing attitude of Wall Street. A positive correlation describes investors obsessed with a weak economy, recession, or depression risks. Whereas negative correlations signify concern with inflation risk.

When the correlation is negative (i.e., rising yields are associated with falling stock prices) and inflation is feared foremost on Wall Street, improved economic numbers often hurt both bonds and stocks since they are perceived as harbingers of increased inflationary potential. However, when deflation or recession is the central focus and the correlation is positive, better economic reports imply less risk of a deflationary abyss or recession pushing both bond yields and stock prices higher.

The economic experience of the 1970s persuaded everyone to fear inflation, and that focus remained dominant for almost two decades after the inflationary spiral peaked in the early 1980s. During that period, a persistently negative correlation between stock prices and bond yields reflected widespread inflation anxiety. News of improved economic growth simply escalated these fears, forcing yields higher and stock prices lower. Because Wall Street suffered from an inflation-psychosis, rising yields were indeed damaging to the stock market.

However, in the early 1990s, Japan entered a deflationary economy followed by the 1997 Asian deflationary abyss, the 1990 Russian deflationary debacle, the 2000 dot-com deflationary meltdown, and the Great Deflationary Recession of 2008. This series of events awakened, and has since sustained, deflation risk/weak economic growth as the predominant investor fear.

This is reflected in Chart 1 by a 1997-98 surge in the correlation, which has subsequently remained mostly positive. Since then, investors haven’t usually viewed rising yields as signaling inflation, but rather, simply a sign of improved economic growth (and thus also good for the stock market).

Consequently, when gauging the impact that rising yields may have on stock prices, it is important to consider whether the investor mindset is primarily focused on inflation (a negative stock-bond correlation) or deflation (a positive stock-bond yield correlation).

Yield Beta Of The Stock Market

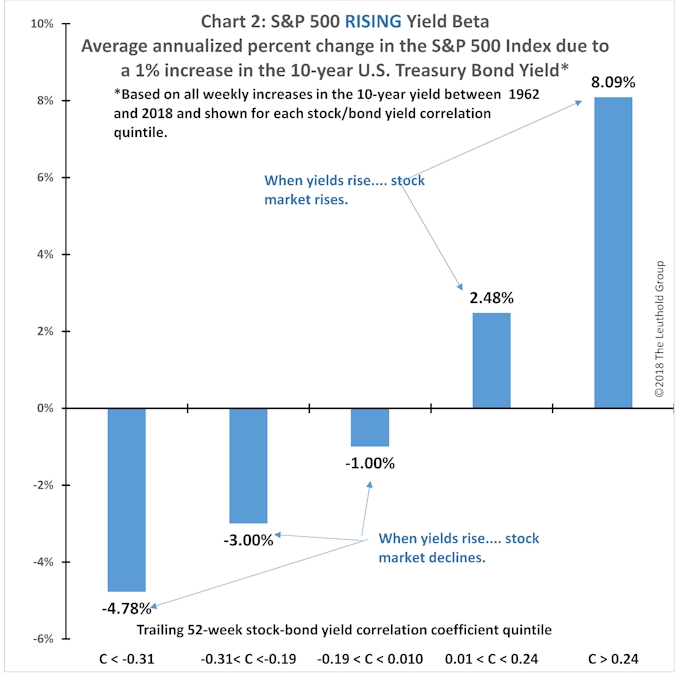

Chart 2 illustrates the relationship between the stock market and rising yields based on the predominate attitude or mindset of Wall Street (i.e., at various levels of the stock-bond yield correlation). Clearly, yield risk in the stock market varies dramatically depending on whether investors are primarily worried about inflation or deflation.

When the correlation is in its highest two quintiles, rising yields are supportive for the stock market. Essentially, higher yields tend to lessen investor fears surrounding weak economic growth. Indeed, as shown in Chart 2, when the correlation between the stock market and bond yields is in the top quintile over the last twelve months, stocks have risen by 8.09% for every 1% increase in the 10-year Treasury bond yield. The rising yield beta for stocks is still 2.48% when the correlation is in its second strongest quintile. Only when the correlation turns negative (in the middle quintile, signifying that inflation is becoming a more dominant concern) do rising yields start to harm stocks. In the middle quintile, the rising yield beta is -1.0%, and worsens to -3.0% and -4.78% in the lowest two quintiles.

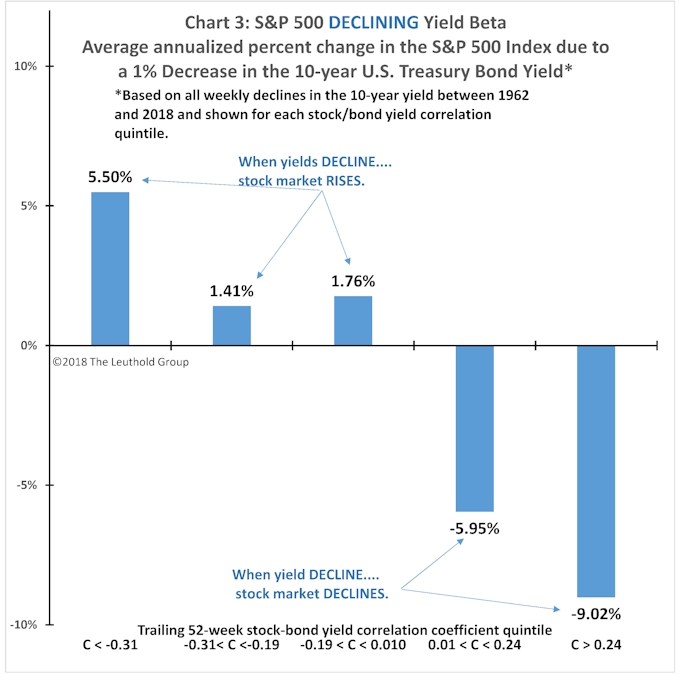

Chart 3 shows that the impact of falling yields is also highly dependent on the mindset implied by the stock-bond yield correlation. Falling yields are associated with a declining stock market when the correlation is positive (because falling yields reinforce fears of weaker economic growth) and are only supportive for the stock market when the correlation turns negative (and falling yields connote an easing of inflation pressures).

Clearly, the relationship between yields and the stock market is not linear. Rising yields can be either good or bad for the stock market and there is no magic yield level which represents a line in the sand for stocks. What is most important is not which way or how much yields are moving, but rather the mindset on Wall Street.

For the last 20 years, the correlation has been positive almost continuously. Therefore, periods of rising yields have mostly been associated with strong stock markets numbing participants’ concerns to the potential risk associated with rising yields. Recently, however, the correlation has weakened to close to zero, one of its lowest readings of the entire recovery. We expect the correlation to soon decline below zero, and into its middle historic quintile for the first time since 2001. While the 10-year yield rising from about 2% to 3% when the correlation was positive created some turbulence in the stock market, how will the stock market react if yields rise toward 4% with a correlation below zero? Is the contemporary investment culture prepared for yield hikes when Wall Street concerns about inflation risk may be more pronounced than worries surrounding weak growth?

Sector Performance And Correlation

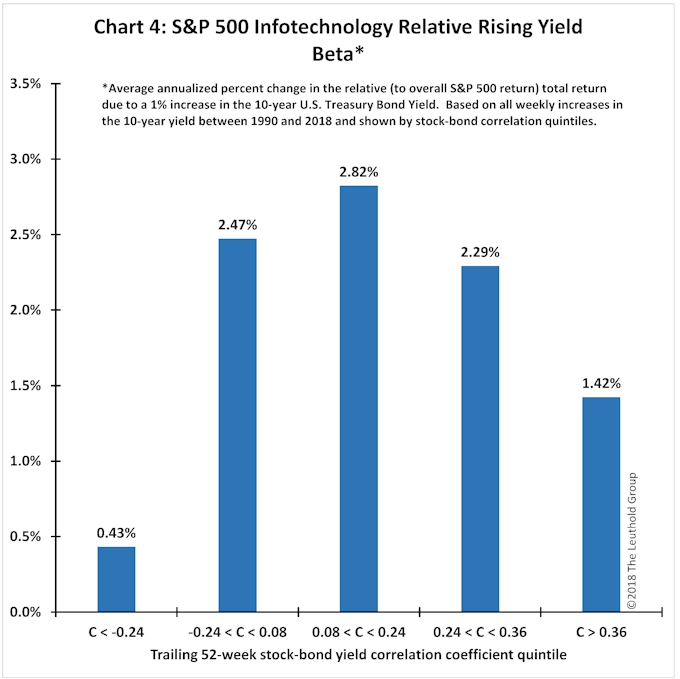

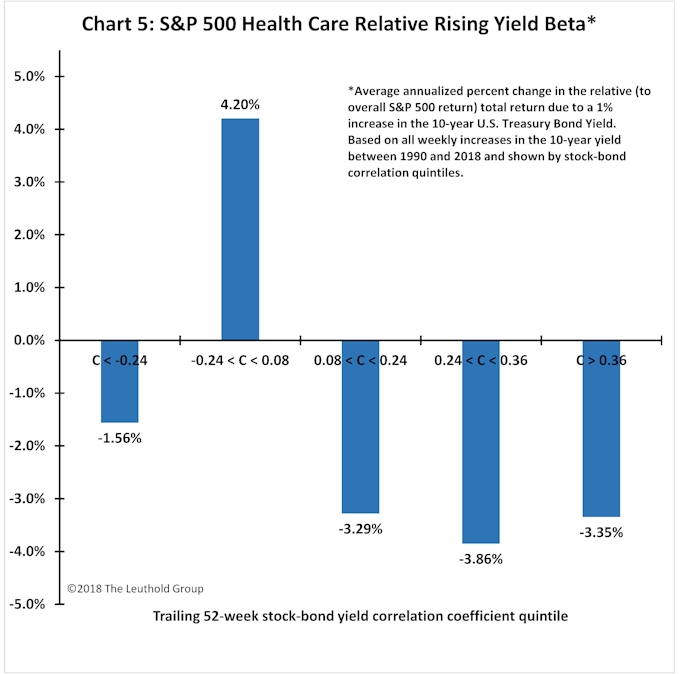

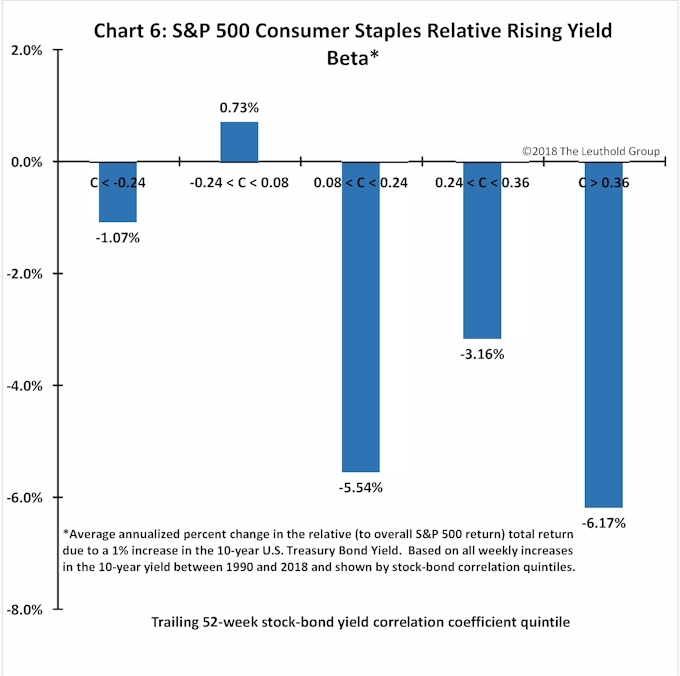

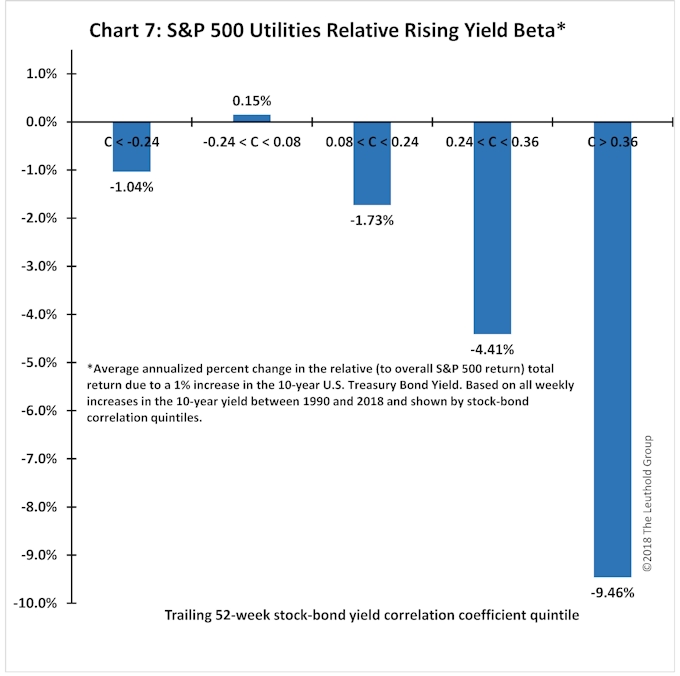

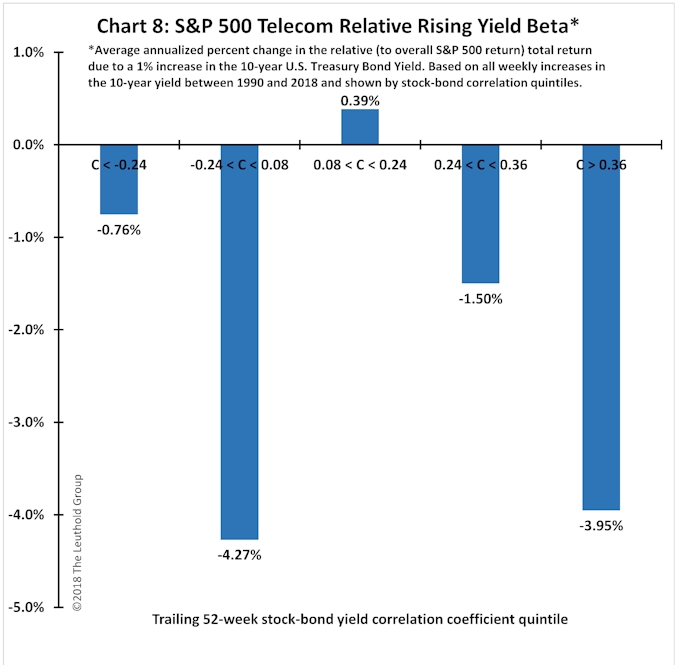

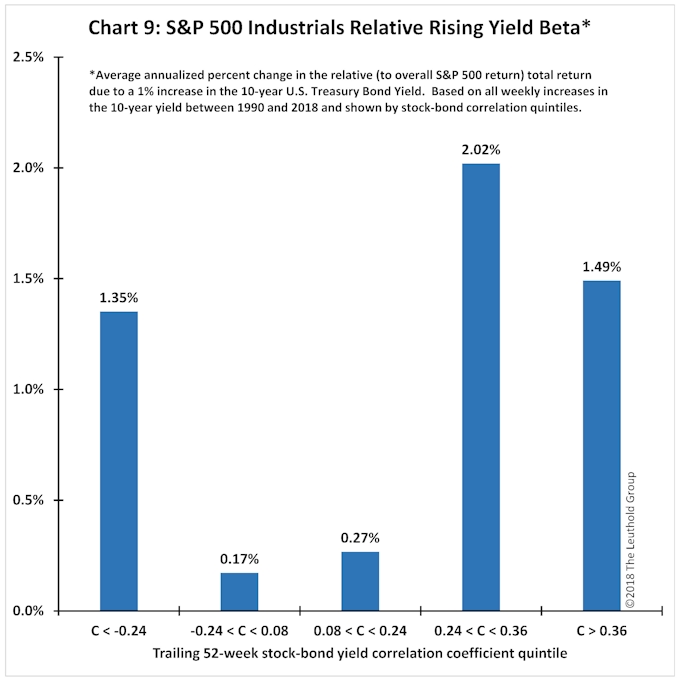

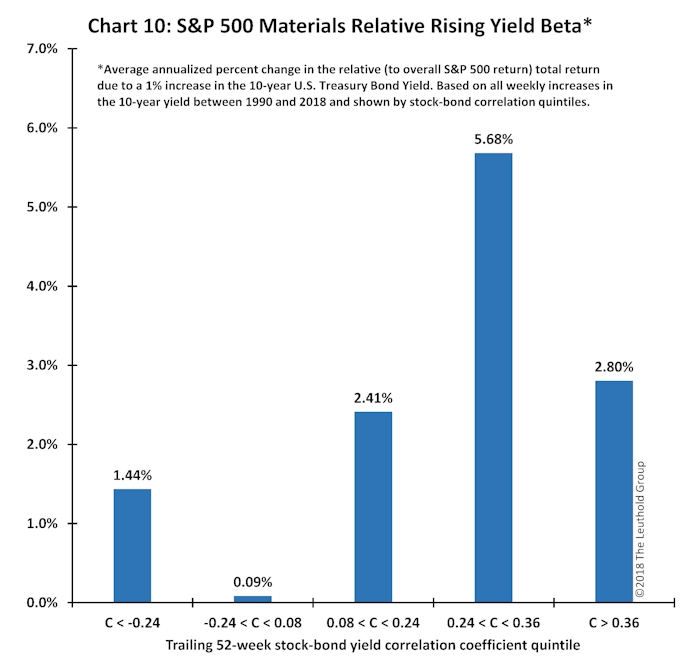

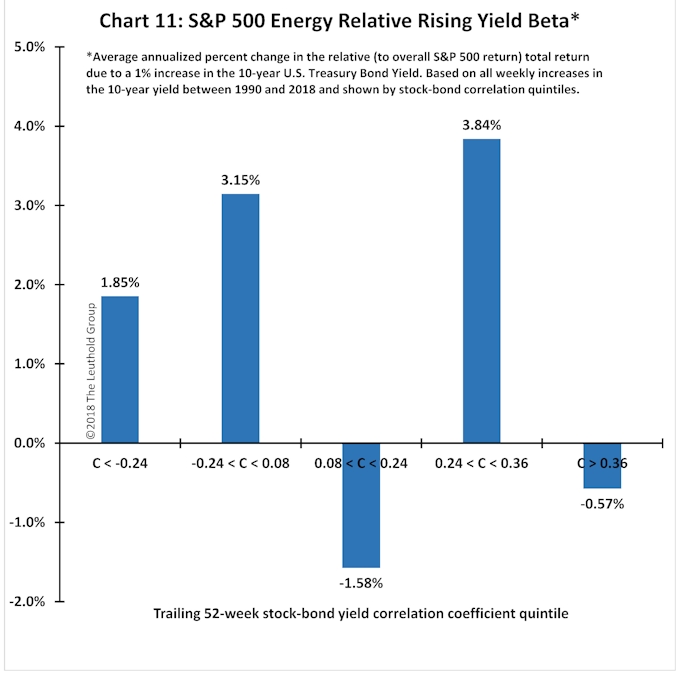

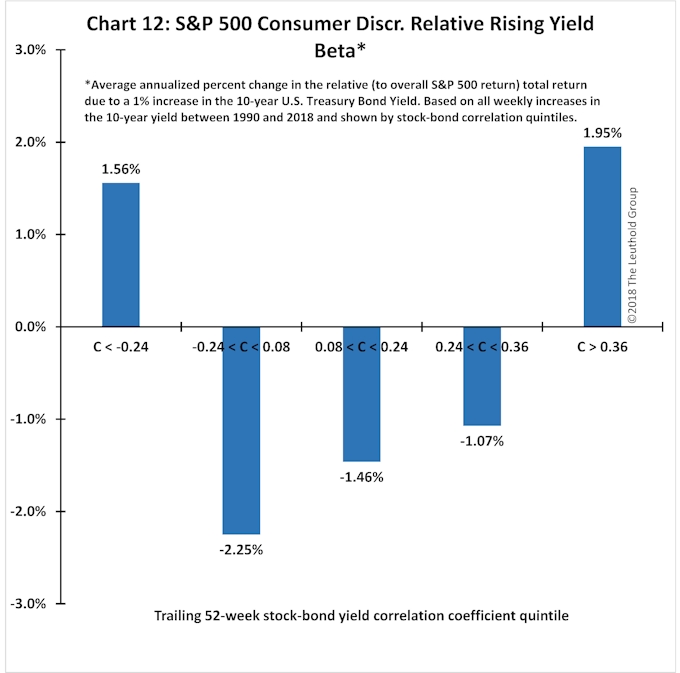

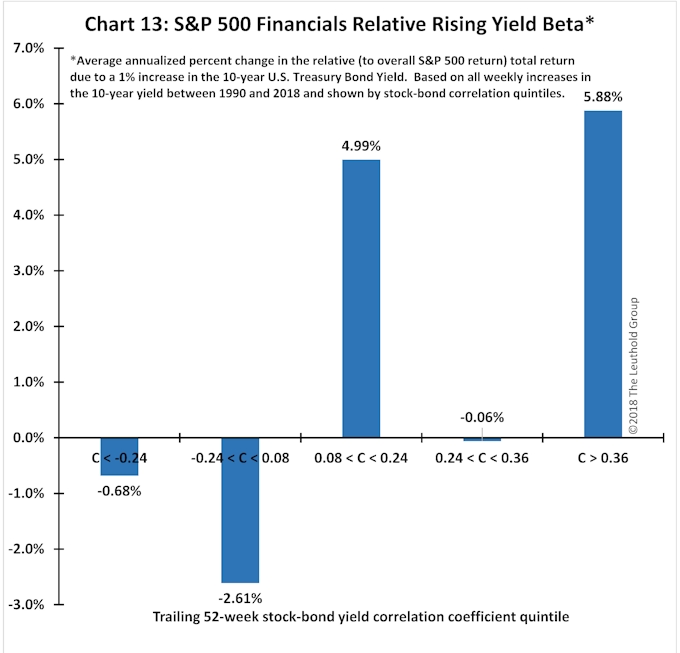

Charts 4-13 illustrate the rising yield betas for the ten broad sectors comprising the S&P 500 between 1990 and 2018. These betas are based on “relative” total return performance. A few comments are noteworthy.

Among all sectors, Technology (Chart 4) is the most consistent performer when yields rise. It is only one of three sectors which exhibits a positive rising yield beta across all correlation quintiles. It responds the best to rising yields when the correlation is in its middle three quintiles. Technology stocks may therefore continue to do well this year even if investor mindset changes as the stock-bond yield correlation turns negative.

By contrast, and not surprisingly, the traditional defensive sectors (i.e., Health Care, Consumer Staples, Utilities, and Telecom) consistently suffer the most from rising yields. In all cases (Charts 5-8), their rising yield betas are negative in all but the second correlation quintile, and in general their betas tend to be more negative compared to other sectors. Moreover, defensive sector betas also tend to be much more negative in the top three correlation quintiles. That is, when investor mentality is more concerned about economic growth, rising yields are more damaging to defensive sectors than are rising yields when inflation is the primary concern. Because the correlation currently appears headed toward the lowest two quintiles, perhaps the damage to defensive stocks from additional yield increases will be far less than it was the last couple years?

Similar to Technology, both Industrials (Chart 9) and Materials (Chart 10) have positive rising yield betas across all correlation quintiles. Energy (Chart 11) tends to have a more varied relationship to rising yields. However, all three industrial/commodity sectors tend to do well when yields rise in the lowest two quintiles of the stock-bond yield correlation. Not surprisingly, these inflation-sensitive sectors perform well in the face of rising yields when Wall Street’s obsession is inflation.

The Consumer Discretionary sector has a unique profile relative to rising yields. Its rising yield beta is strongly positive when the correlation is extremely high or low, but also strongly negative when the correlation is in its middle three quintiles. If growth or inflation concerns are severe, discretionary stocks have tended to do well in the face of rising yields. However, if growth and inflation concerns are not as intense (i.e., correlation in the middle three quintiles) discretionary stocks tend to underperform when yields rise.

Finally, in general, the Financials sector is positively impacted by rising yields when economic growth is the primary concern (i.e., when the correlation is positive) and is negatively impacted when the correlation is in its lowest two quintiles. This suggests the recent leadership of financials, as yields have risen, may reverse if the correlation turns negative.

While we do not understand why sector yield betas are so dependent on the consensus mindset, we do think investors should be mindful that sensitivity to rising yields can vary widely, not only across sectors but also within sectors depending on the stock-bond yield correlation.

Factor Performance And Correlation

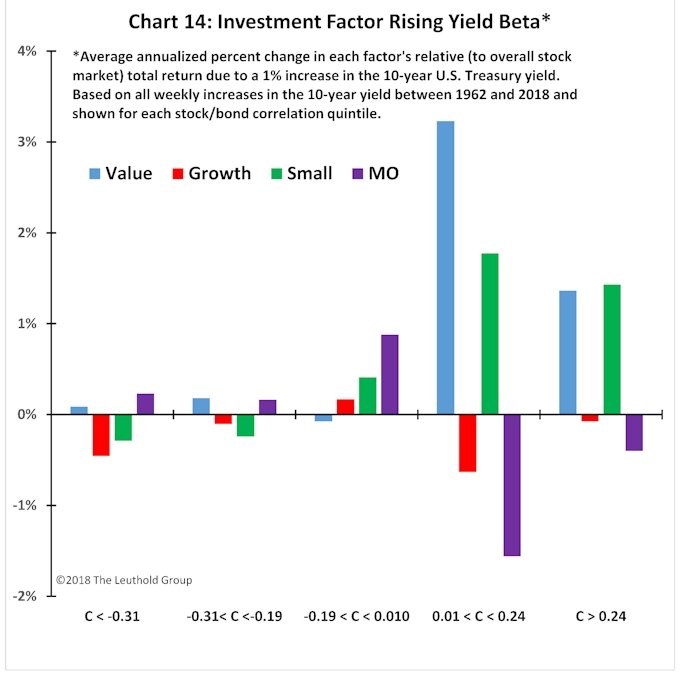

Chart 14 shows the yield sensitivities of investment factors are also impacted by the mindset on Wall Street. It illustrates the rising yield beta sensitivity across the five quintiles of the stock-bond yield correlation since 1962 for value, growth, small-cap, and momentum investing.

The only striking conclusion is that variability of factor relative returns to rising yields is far more pronounced when the correlation coefficient is in the top two quintiles! Moreover, when the correlation is in its lowest two quintiles, factor relative return rising- yield betas hover near zero. That is, negative stock-bond yield correlations, for reasons we do not understand, tend to make factor returns insensitive to rising yields?

Summary

Equity investors increasingly worry about yield risk. Are they nearing a level which could topple the stock market? Or, since earnings performance appears very healthy, do yields need to rise significantly more before threatening the stock market?

The impact of rising yields on the stock market is not about a key yield level, nor is it critically dependent on how much yields have risen. Rather, the stock market’s beta to rising yields varies depending on the prevailing consensus attitude regarding growth and inflation. For much of the last 20 years, and during the contemporary economic recovery, the predominant concern has been weak growth and deflation. Consequently, the correlation has been persistently positive, implying that rising yields have supported better stock returns. Since the rising yield beta in the stock market has been positive for so long, investors’ yield risk sensitivities have been dulled. Indeed, excuses are frequently heard as to why rising yields will not cause the stock market to stumble. For example, yields are coming from such low levels, they are still very low relative to the rate of inflation, they can’t rise much because yields in the rest of the world are lower, and finally, since earnings are so good, the stock market can weather higher yields.

However, concerns about inflation are growing quickly. Recently, the stock-bond yield correlation has declined to near its lowest level of this recovery, and one of the lowest levels in the last 20 years. Moreover, we suspect it will soon turn negative for the first time since 2001! As Wall Street worries more about inflation than it does about growth, expect the stock market’s rising yield beta to worsen.

As the 10-year yield rose from 2% to 3%, the impact on the stock market was muted because the correlation between stocks and bond yields has been positive. However, if the correlation soon turns negative and yields continue climbing, expect a more adverse reaction from the stock market.

For stock investors, yield is a state of mind. When the 10-year yield rose from 2% to 3%, Wall Street was in a ‘New York state of mind’—Party Hardy! Today though, will a continued rise in yields soon start to reflect a new ‘stock market state of mind’—a Hangover?